[初めに]

頭脳明晰な方・難しいことを考えるのが好きな方、よろしければぜひお力を貸してください。。。🙇♂️

唐突ですが、あなたには「生涯忘れられない本」というものがあるでしょうか?

僕が仮にこの質問を受けたとしたら間違いなく真っ先に名前が挙がるのがこちらの本です。

ZEN AND THE ART OF MOTORCYCLE MAINTENANCE

An Inquiry into Values

『禅とオートバイ修理技術 – 価値の探究』

27カ国語に訳され世界中で累計500万部以上を売り上げたとされているこの本は、1974年に ロバート·メナード·パーシグという1人の天才によって世に放たれ (2017年に他界)、アメリカの若者たちを中心に瞬く間に熱狂的なファンを獲得し、10数年に渡ってベストセラーリストに名を連ねました。

何がそんなに読者を惹きつけるのか。

まず、なぜかクセになる超難解な著者の論理思考と人間知性への気持ちいほどに鋭い考察があげられます。ただ個人的にはそれ以上に、いつからともなく始まり21世紀の今日に至るまで、依然として現代社会に蔓延ってる人々の心の問題。この問題に対しパーシグ氏が「Qality-クオリティ」という不思議な言葉への探究を通じて、彼なりの答えを世界に示したこと、そしてその過程で繰り広げた高次元の思考体系構築の営み、それでいてどこか慈悲深く人間味のある彼の言葉の数々が多くの人々の琴線に触れたのだと信じています。

僕はこの文章を読んでくれているあなたへお願いをしようと思ってこの記事を書いています。それは、パーシグ氏が残した文章を僕がきちんと理解できているかチェックをしてほしい、この本を通じて著者が意図していることは何なのかを一緒に考えてほしいというものです。僕はこの本を少なくとも何十回、音声を含めると100回以上は読んでいると思います。それでも今もなお、この本の内容を理解したという確証が持てないというのが正直な感想です。

何も大それた事を試みようとしているわけではありませんが、ただ、この IQ170を誇ったロバート·パーシグ氏の超越した論理思考の旅をいくつか整理し、彼が本当に伝えようとしていた内容が自分の頭で理解できているのかが知りたい。また、それを踏まえた上で彼が残した言葉を、功績を、今後少しでも多くの人と共有したい。そんな想いでこの本の内容を紹介しています。この本を読んだことがある。または、これから紹介する文章を読んで何か感じたことがある。翻訳のこの部分が間違っている。もっとこっちの言葉に替えた方がいいなど、どんな些細なことでも構いませんので、ぜひ僕にSNSやブログのお問い合わせで感想や意見を教えてください。それでは早速、一緒にロバート·パーシグ氏の世界へまいりましょう!

と言いたいところですが、

いきなり本の文章に入る前にいくつか最低限知っておくべき内容をここで簡単に紹介しておきます。

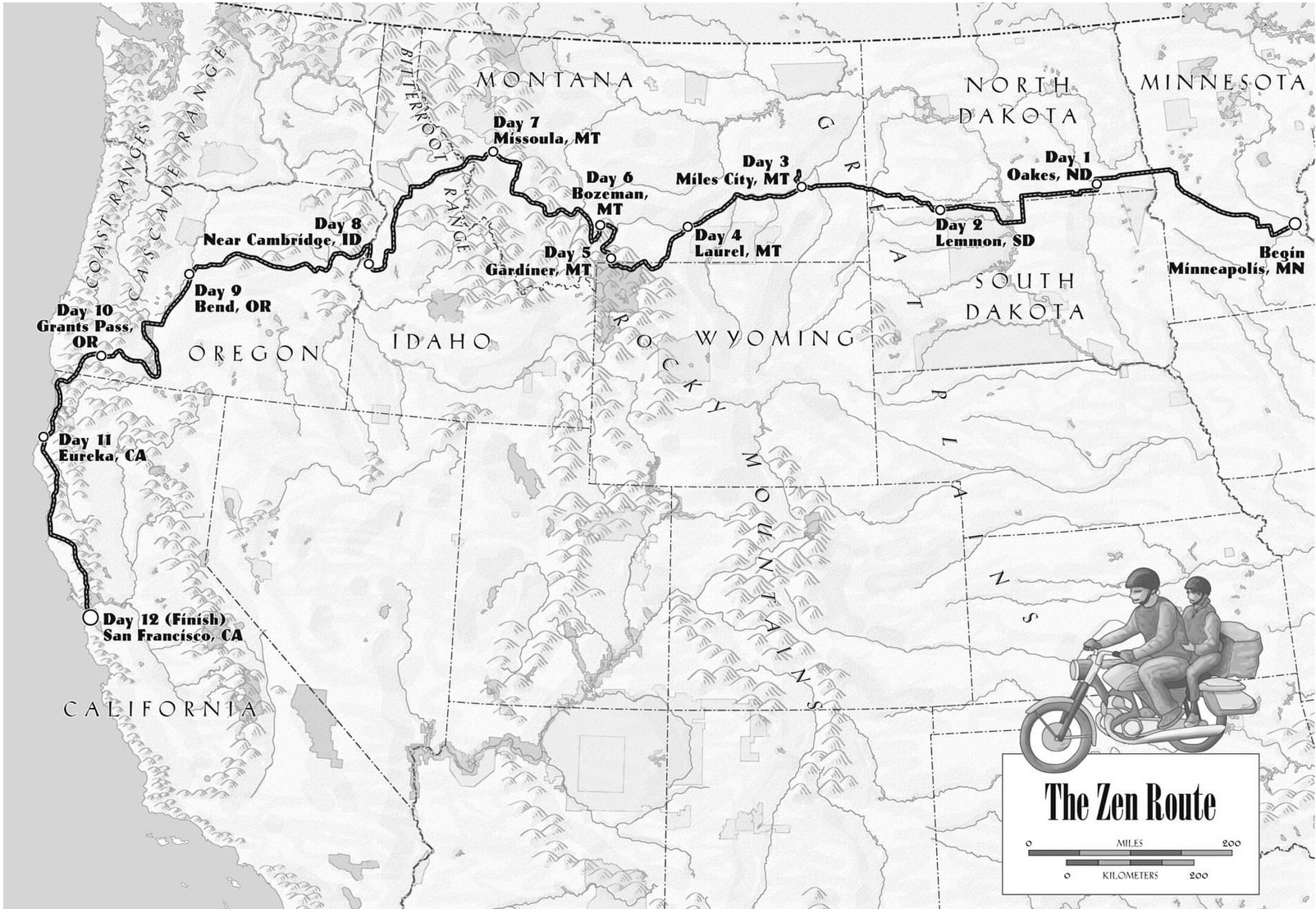

この『禅とオートバイ修理技術 – 価値の探究』という本の物語は、主人公と息子のクリス (当時: 11歳)が架空の17日間で行ったアメリカ横断の旅をベースに進行していきます。また、最初の9日間は、主人公と親しい友人·ジョンに加え、妻のシルビア (=サザーランド夫妻) もこのバイクの旅に同行します。

『旅のルート』

【出典: wikipedia】

物語の主人公(=ナレーター)は現実世界では明らかにパーシグ氏本人ですが、本の中では終始特定されていない「私 = 1人称」が語り手の役割を担います。パーシグ氏いわく、「読み物として面白くするためにいくつか変更した点はあるが物語の基盤は事実に基づいたものだ。」としていますので、物語の中で起こった出来事の大半は現実のものだと捉えても支障はないでしょう。

さて、それではここからが本番です。

パーシグ氏とクリスの長いバイクの旅の途中、彼の頭の中を駆け巡っていた思想とは。。

現代人の幽霊の話

最初の文章は、旅の序盤に彼らが立ち寄ったとあるモーテル (道路沿いにある自動車旅行をする人のための宿泊所) での4人の会話です。

日本語翻訳はこちらから

That Ghost Story

Chris wonders what we should do next. Nothing tires this kid. The newness and strangeness of the motel surroundings excite him and he wants us to sing songs as they did at camp.

“We’re not very good at songs,” John says.

“Let’s tell stories then,” Chris says. He thinks for a while. “Do you know any good ghost stories? All the kids in our cabin used to tell ghost stories at night.”

“You tell us some,” John says.

And he does. They are kind of fun to hear. Some of them I haven’t heard since I was his age. I tell him so, and Chris wants to hear some of mine, but I can’t remember any.

After a while he says, “Do you believe in ghosts?”

“No,” I say.

“Why not?”

“Because they are un-sci-en-ti-fic.”

The way I say this makes John smile. “They contain no matter,” I continue, “and have no energy and therefore, according to the laws of science, do not exist except in people’s minds.”

The whiskey, the fatigue and the wind in the trees start mixing in my mind. “Of course,” I add, “the laws of science contain no matter and have no energy either and therefore do not exist except in people’s minds. It’s best to be completely scientific about the whole thing and refuse to believe in either ghosts or the laws of science. That way you’re safe. That doesn’t leave you very much to believe in, but that’s scientific too.”

“I don’t know what you’re talking about,” Chris says.

“I’m being kind of facetious.”

Chris gets frustrated when I talk like this, but I don’t think it hurts him.

“One of the kids at YMCA camp says he believes in ghosts.”

“He was just spoofing you.”

“No, he wasn’t. He said that when people haven’t been buried right, their ghosts come back to haunt people. He really believes in that.”

“He was just spoofing you,” I repeat.

“What’s his name?” Sylvia says.

“Tom White Bear.”

John and I exchange looks, suddenly recognizing the same thing.

“Ohhh, Indian!” he says.

I laugh. “I guess I’m going to have to take that back a little,” I say. “I was thinking of European ghosts.”

“What’s the difference?”

John roars with laughter. “He’s got you,” he says.

I think a little and say, “Well, Indians sometimes have a different way of looking at things, which I’m not saying is completely wrong. Science isn’t part of the Indian tradition.”

“Tom White Bear said his mother and dad told him not to believe all that stuff. But he said his grandmother whispered it was true anyway, so he believes it.”

He looks at me pleadingly. He really does want to know things sometimes. Being facetious is not being a very good father.“Sure,” I say, reversing myself, “I believe in ghosts too.”

Now John and Sylvia look at me peculiarly. I see I’m not going to get out of this one easily and brace myself for a long explanation.“It’s completely natural,” I say, “to think of Europeans who believed in ghosts or Indians who believed in ghosts as ignorant. The scientific point of view has wiped out every other view to a point where they all seem primitive, so that if a person today talks about ghosts or spirits he is considered ignorant or maybe nutty. It’s just all but completely impossible to imagine a world where ghosts can actually exist.”

John nods affirmatively and I continue.

“My own opinion is that the intellect of modern man isn’t that superior. IQs aren’t that much different. Those Indians and medieval men were just as intelligent as we are, but the context in which they thought was completely different. Within that context of thought, ghosts and spirits are quite as real as atoms, particles, photons and quants are to a modern man. In that sense I believe in ghosts. Modern man has his ghosts and spirits too, you know.”

“What?”

“Oh, the laws of physics and of logic — the number system — the principle of algebraic substitution. These are ghosts. We just believe in them so thoroughly they seem real.”

“They seem real to me,” John says.

“I don’t get it,” says Chris.

So I go on.“For example, it seems completely natural to presume that gravitation and the law of gravitation existed before Isaac Newton. It would sound nutty to think that until the seventeenth century there was no gravity.”

“Of course.”

“So when did this law start? Has it always existed?”

John is frowning, wondering what I am getting at.

“What I’m driving at,” I say, “is the notion that before the beginning of the earth, before the sun and the stars were formed, before the primal generation of anything, the law of gravity existed.”

“Sure.”

“Sitting there, having no mass of its own, no energy of its own, not in anyone’s mind because there wasn’t anyone, not in space because there was no space either, not anywhere…this law of gravity still existed?”

Now John seems not so sure.

“If that law of gravity existed,” I say, “I honestly don’t know what a thing has to do to be nonexistent. It seems to me that law of gravity has passed every test of nonexistence there is. You cannot think of a single attribute of nonexistence that that law of gravity didn’t have. Or a single scientific attribute of existence it did have. And yet it is still ‘common sense’ to believe that it existed.”John says, “I guess I’d have to think about it.”

“Well, I predict that if you think about it long enough you will find yourself going round and round and round and round until you finally reach only one possible, rational, intelligent conclusion. The law of gravity and gravity itself did not exist before Isaac Newton. No other conclusion makes sense.

“And what that means,” I say before he can interrupt, “and what that means is that that law of gravity exists nowhere except in people’s heads! It’s a ghost! We are all of us very arrogant and conceited about running down other people’s ghosts but just as ignorant and barbaric and superstitious about our own.”“Why does everybody believe in the law of gravity then?”

“Mass hypnosis. In a very orthodox form known as ‘education.’”

“You mean the teacher is hypnotizing the kids into believing the law of gravity?”

“Sure.”

“That’s absurd.”“You’ve heard of the importance of eye contact in the classroom? Every educationist emphasizes it. No educationist explains it.”

John shakes his head and pours me another drink. He puts his hand over his mouth and in a mock aside says to Sylvia, “You know, most of the time he seems like such a normal guy.”

I counter, “That’s the first normal thing I’ve said in weeks. The rest of the time I’m feigning twentieth-century lunacy just like you are. So as not to draw attention to myself.

“But I’ll repeat it for you,” I say. “We believe the disembodied words of Sir Isaac Newton were sitting in the middle of nowhere billions of years before he was born and that magically he discovered these words. They were always there, even when they applied to nothing. Gradually the world came into being and then they applied to it. In fact, those words themselves were what formed the world. That, John, is ridiculous.

“The problem, the contradiction the scientists are stuck with, is that of mind. Mind has no matter or energy but they can’t escape its predominance over everything they do. Logic exists in the mind. Numbers exist only in the mind. I don’t get upset when scientists say that ghosts exist in the mind. It’s that only that gets me. Science is only in your mind too, it’s just that that doesn’t make it bad. Or ghosts either.”

They are just looking at me so I continue: “Laws of nature are human inventions, like ghosts. Laws of logic, of mathematics are also human inventions, like ghosts. The whole blessed thing is a human invention, including the idea that it isn’t a human invention. The world has no existence whatsoever outside the human imagination. It’s all a ghost, and in antiquity was so recognized as a ghost, the whole blessed world we live in. It’s run by ghosts. We see what we see because these ghosts show it to us, ghosts of Moses and Christ and the Buddha, and Plato, and Descartes, and Rousseau and Jefferson and Lincoln, on and on and on. Isaac Newton is a very good ghost. One of the best. Your common sense is nothing more than the voices of thousands and thousands of these ghosts from the past. Ghosts and more ghosts. Ghosts trying to find their place among the living.”

John looks too much in thought to speak. But Sylvia is excited. “Where do you get all these ideas?” she asks.

I am about to answer them but then do not. I have a feeling of having already pushed it to the limit, maybe beyond, and it is time to drop it.

After a while John says, “It’ll be good to see the mountains again.” “Yes, it will,” I agree. “one last drink to that!”

We finish it and are off to our rooms.日本語翻訳はこちらから

以下、かなり個人的な見解になりますのでご了承ください。

あえて先に忠告させて頂くことがあるとすれば「この高次元の思考について来れない人は読んでもらわなくて結構」と言わんばかりに読者を突き放す難解な部分が多々あります。この本の感想を書いているブログ等もいくつか見かけましたが、相当な学歴をお持ちの方でも「哲学的な部分は何が言いたいのか分からなかった。なぜそんなことを気に掛ける必要があるのか不明。」などといった考察が多く、未だにパーシグ氏の考えの核心を捉えていると思える考察が少ないのが現状です。ただ、一つ言えるのは、日本だけでなく世界中で「この本を読んで物事に関する考え方が180°変わった。」と言う人は少なくありません。僕もその1人です。それほどに多くの人の心に響き、人の奥底に眠る深い思考を目覚めさせてくれる一冊だと思います。